Peter Lynch once said, “Market timing is speculating and it rarely, if ever, pays off.” In the long-run stock prices rise, but in the short-run they are notoriously hard to forecast. No matter what increments of time are examined – days, weeks, or years – stock markets tend to go up roughly two thirds of the time.

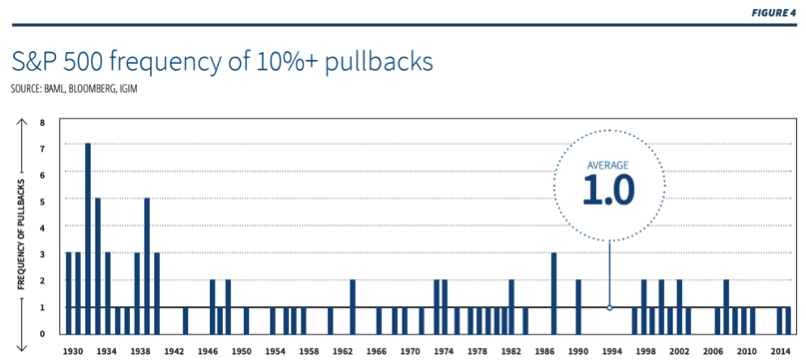

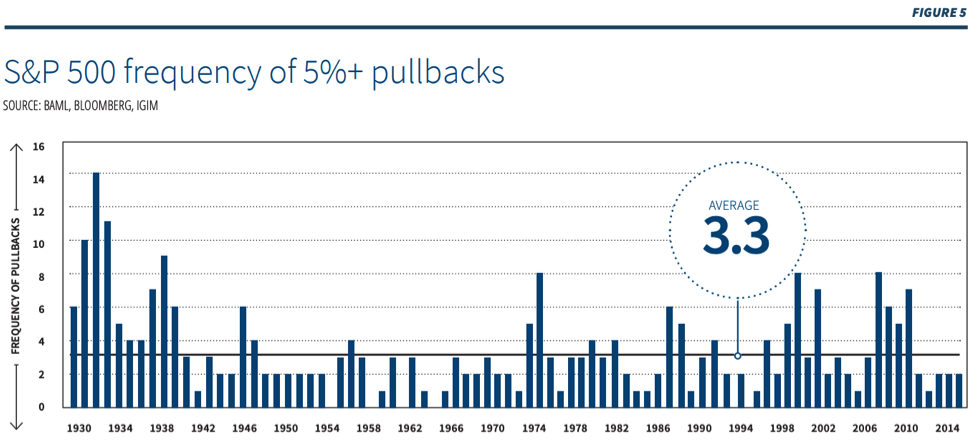

With the odds so overwhelmingly in favour of gains, why do so many investors fight those odds trying market timing? Market pullbacks are frequent, and avoiding just a few of them could potentially add significantly to investment results.

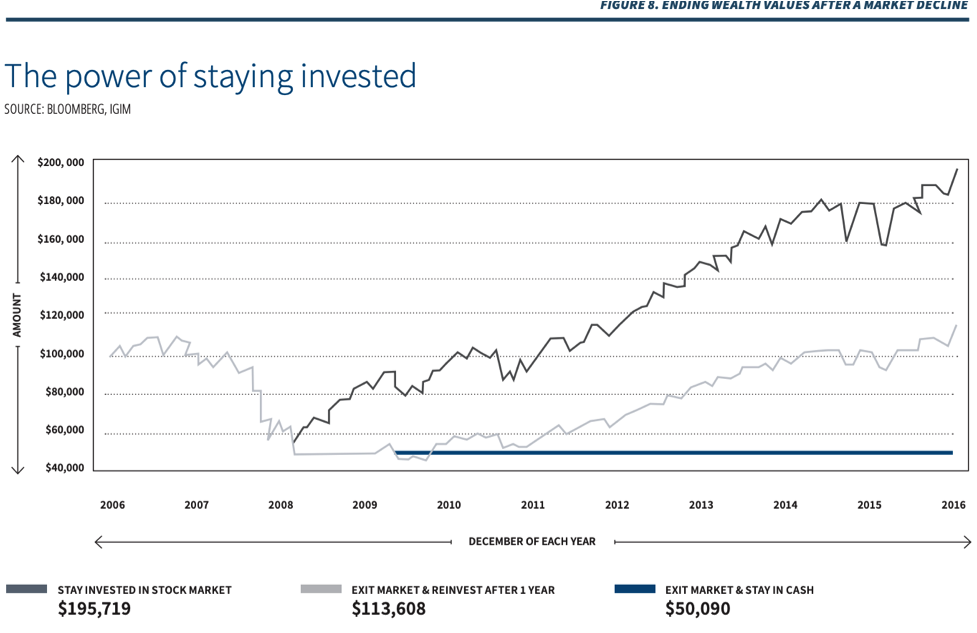

But attempts at market timing to avoid pullbacks more often lead to missing out on significant advances. And missing out on just a few of these can be devastating for investment results. In almost all circumstances, the fundamental key to successful investing is having the discipline to stay invested. Time in the market, rather than market timing, is what creates wealth.

Stocks tend to go up

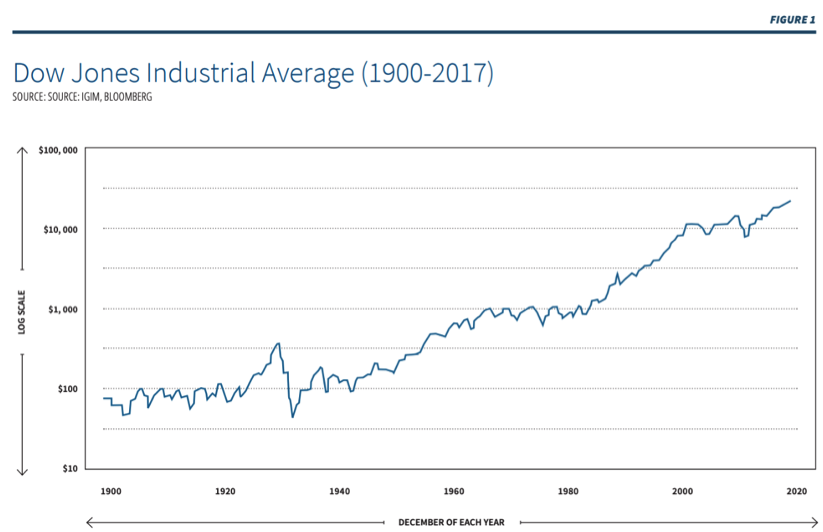

Figure 1, below, shows US equity returns over the course of the last 120 years. With a long enough perspective, the most dramatic equity market selloffs (with the notable exception of the 1929 crash) begin to look like mere noise in a seemingly relentless advance. This includes the 2008 “great recession”, the bursting of the dot-com bubble and even the crash of 1987.

This really illustrates the consistency of positive long-term returns in equities. In fact, according to Merrill Lynch, $1 invested in US large company stocks in 1824, with dividends reinvested, would have been worth almost $7 million by the end of 2016. Granted, two hundred years is not a realistic time horizon, but many investors today experienced the great bull market of 1982 to 1999, where US stocks returned 1654%. And more recently, US large caps returned over 250% since the low of March 2009. With a decent time horizon, market timing shouldn’t even need to be considered.