Over 5.3 million refugees have fled Ukraine to neighbouring Poland, with an additional one million fleeing to the U.K. and other parts of Europe. When the conflict started, the world watched and waited to see how this would affect the global supply of food and energy exports from across eastern Europe. Russia is a major oil producer, exporting 85% of its production to Europe and China at the time of the invasion.

Global benchmark crude prices surged following the invasion, causing oil to trade above US$100 per barrel, and swung wildly in the weeks to follow. This brought major supply and inventory shortages, which led many to believe that commodity prices would continue to push inflation to elevated levels.

Crisis inflation or disinflation?

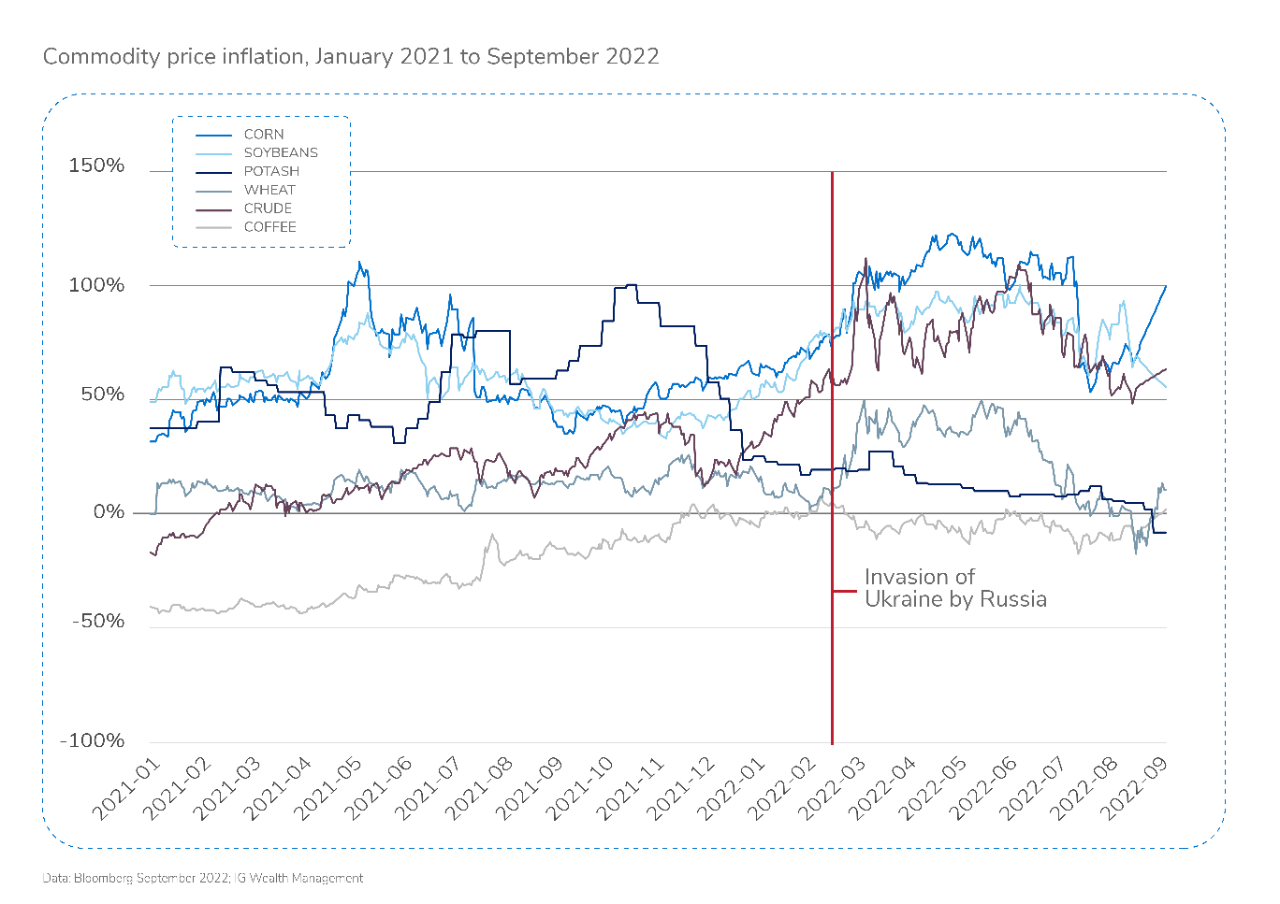

When we look back at the data from January 2021 to the present, the idea that commodities were a catalyst of higher inflation and that they would create havoc in the financial markets seems to have been overplayed. In fact, over the past seven months, the level of commodity prices has decreased from pre-war levels. Also, food and energy price appreciation was already very strong, following the rebound in economic activity from the increase in global money supply and the rapid reopening in 2021.

Yes, it’s reasonable to expect some short-term disruption within commodity prices when there is conflict between high-exporting economies. The economic and political sanctions against Russia did not help energy prices either. Oil-producing nations increased their production to maximum output levels, and in March, U.S. President Joe Biden began releasing one million barrels of crude oil per day over six months, from his country’s Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR). The historic release of SPR crude provided the U.S. economy with a record amount of crude oil supply, which will continue until the end of October 2022.

Meanwhile, European economies are adjusting to the changing energy markets, and consumers there, as well as in North America, have been hit with higher fuel and food prices all summer. However, since August, we have seen prices of major commodities (wheat, soybeans, crude oil, corn and potash) fall to pre-war levels.

The chart below shows the spike in several commodity values up to July, along with their significant decreases in August.